I discovered the other day that Indian thought is sinking into my mind deeper than I realized. It was late at night and I was standing in the last town on the western extreme of India. The hotel manager knew he had the lowest rates in town, but also knew he could milk me for every penny below the price of his competitors. As I inspected the room and prepared to launch into my "good-humored outrage" routine to lower the prices, a small rodent scurried out from under the bed and fled towards the shower. Unfazed, I dropped my act and cooly said "There is mouse. 200 rupee discount." My reasoning proved unassailable.

Dwarka is yet another holy city, one of the twelve or so holiest places in Hinduism. It marks the West of the four cardinal direction temples at the extremes of the country, and was also the resplendent capital of Krishna's kingdom when he walked the earth. Though no remains of this ancient capital can be seen, there are many ruins sunken off the coast. Before earthquakes and sedimentation shrunk the Saurashtra peninsula and enlarged Kutch, this really was the end of the Hindu world, and having traveled hours and hours across the sparse countryside to get here and look out at the sun-mirror sea, its not hard to see why the early Hindus were content to label this the end of the gods' concerns. Of course, even in ancient times they knew that it wasn't really the end of the world. Asking Hindu pilgrims in Dwarka today, I found that the modern age and globalization have had little effect on their esteem for the place.

"The gods made the world round," a seller of religious trinkets told me "but this is the true end." And indeed, to many of the Hindu people I spoke with, it was a solid fact that beyond the temples looming over Dwarka's lonely beach lies only sea and the land beyond which belongs almost to a different planet.

A jolly bearded saddhu approached me and I asked him the same question.

"You see, after Dwaraka there is only empty. Empty, empty, and then bad."

"Bad?" I asked.

"Arabs."

"Arabs bad?" I continued, containing a chuckle as I tried to provoke a tirade.

Raising his index finger he quickly and cheerily instructed me "Very most Muslim peoples." He then stared at me with a smile on his face, content in the thorough impartation of his wisdom.

I made it my business very first thing in the morning to visit Krishna's temple. Its massive spire soared some sev...

OK, actually I made it my business first thing in the morning to go to the beach and stare victoriously at the Arabian Sea. It was coincidentally the first time I have laid eyes upon the Indian Ocean, and I felt that doing so in Dwarka would hold some deeper meaning. I was dissapointed in this regard, as it looked very much like an ordinary, albeit isolated, beach with a European-style lighthouse. The sea itself of course looked much as you would expect it to: blue with a hint of grey, and then a horizon. I don't know why I thought it might be otherwise. Denied this special triumph I took my next order of business, which was releiving myself into the Arabian Sea. I can now say, my friends, that I have left a little taste of myself in each of the Earth's four mighty oceans: Atlantic, Pacific, Arctic, and now Indian. World domination is but a step away.

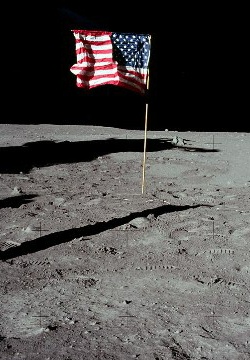

I made it my business earlyish in the morning to visit Krishna's temple. Its massive spire soared some seven stories over the rest of the town and a triumphant flag billowed from its pinnacle. Indian army troops guarded the perimeter with heavy machine guns, overlooking a bustling milieu of pilgrims, merchants, and cows. Passing throught the stringent security I made my way into the temple precinct. Within I found an intoxicating spectacle of bhramins, disciples, monks, saddhus, and other pilgrims in a mystifying diversity of costume. Alongside the standard orange rags were men with their entire faces painted yellow, priests in white skirts with pink flowered shoulder pads, haircuts ranging from fearsome dreadlocks to baldness to the daintiest of Shivaite hair-strands. There were a group of albinos with their hair colored orange and a group of young students receiving waves of white paint on their faces. A saddhu with a bouncing belly danced in circles, tapping the ground with his stick and repeating praises with an increasing shortness of breath. A group of women dressed in dark blue saris sat on the ground gazing at the top of the spire. I looked up and watched as a tiny little man climbed a giant rope to a platform swaying on the flagpole and began changing the standard from one of yellow and blue to one of purple and white. As the flag finally unfurled a great cheer arose from the crowd and their eyes followed something downwards, watching I did not know what. Mine remained fixed on the flag and I was thus taken by complete surprise when sprightly men hurled themselves around my body, nose-diving into the stone pavement, then rising and shouting with joy as they and the blue-sari women emerged from the scrum with shards of shattered coconuts.

I have asked, and travel writing does not offer hazard pay for dodging ritually dropped coconuts. This gig has no perks.

From the Krishna temple I headed down an alley to the coast. There was one final temple there and a row of ghats topped with a dozen or so minor shrines. The standard for priestly behavior here was considerably more lax. Pot-bellied brahmins milled about in orange robes and wifebeater T's, scratching their armpits and wiping spots of spilled dahl off their chests. Some of these I recognized from the temple earlier. The lesser shrines were clearly where the priests went to kick back. From behind quivers of incense sticks in almost every shrine came the tinny sound of transistor radios, all tuned to the same cricket match, which the brahmins listened to intently, listlessly responding to the needs of local worshippers who came to pay their respects to the gods. If there was ever an illustration of the deficiencies of having a hereditary caste of clergy this was it.

You may recall that your humble correspondent is engaged in a blood feud with India's cows. You may also recall that deep in the Thar Desert I delivered a crippling pimp-slap to the Last Cow In India. I must confess, as satisfying as it was, that that cow's location was a mere accident of cartography. Though doubtless the last cow in that desolate region before the Pakistani border, could there not be a thousand other cows similarly located along the length of India's frontier? My satisfaction was not complete. In Dwarka, though, I stood upon India's spiritual frontier, the place definitively marked as the western edge of Hindudom. I think you see where this is going.

As I loitered on the ghats, I noticed a pair of cows molesting some picnicking women, who responded by hitting the cows in the face with shoes. I waiting, biding my time for the perfect moment. At last, one cow broke away and headed towards the end of the ghats where the estuary met the sea at a spired temple and made a beeline for a cart of juicy cabbages. As the cabbage-wallah scrambled to protect his goods I, superhero-like in my timely intervention, swept in a smacked the cow heartily upon the gut, driving it to the very edge of the stone promenade and the temple wall, trapping what was truly and unquestionably the Last Cow In India inches from a fall into the lapping waves of the Arabian Sea. I then delivered a single patronizing baby-slap to the snout and strolled away as a few dozen Indians stared and wondered what I looked so damn smug about. A handful asked me directly while I was smiling so oddly.

"You could never understand."

It was now past sundown. Around the bend from the ghats, the beach stretched along the side of town and ended in a small rocky point. A group of Hindus stood huddled around a bundle on the ground. Through their legs I saw the supine form in its delicate green shroud. It was a corpse. Soon after they carried the body off towards the rocks where two crematory fires already roared. They placed the stretcher on the wood and lit the fire with burning brush. Dwarka is a place of strong darshan, where the barrier between the world of men and gods is especially penetrable. As the mourners stood patiently watching the slow dissapearance of their loved ones, none of them wept or seemed to grieve. With the mighty Lord Krishna's throne somewhere beneath the glistening star-stroked waves offshore, they could perhaps seek solace in the words with which he soothed the despondent Arjuna, and maybe just as they knew that where they stood was not really the end of the world, that death isn't the last to be seen of this world either.

Dec 11, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Hey Ghostface:

ReplyDeleteI've been following your blog for a while now, never fails to entertain. Funny anecdote about the mouse, but also not-bad luck, because Ganesh supposedly rides around on a mouse.

(how exactly an elephant rides a mouse is just one of those divine mysteries, I guess)

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteYour Questions Answered!:

ReplyDelete1)Ganesh is not an elephant, he merely has an elephant's head, a replacement for the one his father Shiva accidentally cut off.

2)Ganesh shrinks to the mouse's size. At least that's what a monk told me.

I just found out there are 5 oceans, not 4 - you should get to work on relieving yourself in the Southern Ocean.

ReplyDelete